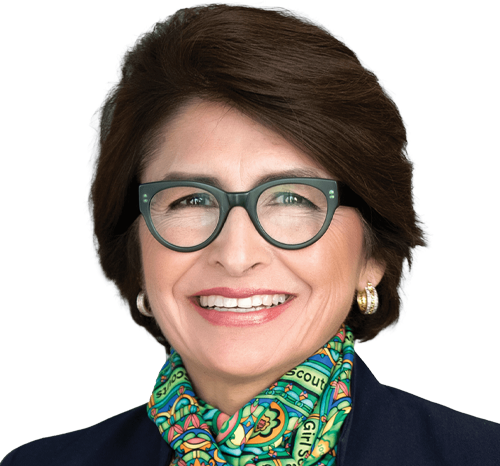

From living on a dirt street in rural new Mexico living in poverty as her parents struggled paycheck to paycheck, to rocket scientist, CEO, board member extraordinaire and bestselling author, Sylvia Acevedo’s story is an inspiring story of transformation.

Thanks for listening!

We love our listeners! Drop us a line or give us guest suggestions here.

Links

Bridges Out of Poverty

“Path to The Stars:” My Journey From Girl Scout to Rocket Scientist. (A Middle School Memoir)

Sylvia Acevedo Speaker Contact Info

Quotes

On writing “Path to The Stars:” My Journey From Girl Scout to Rocket Scientist

“I chose middle school because the way the world is evolving, science and technology are embedded in everything that we’re doing, and you need to have at least a modicum of understanding about science and technology, and middle school is kind of that last time you can choose those electives and that really what is like an inflection point in your life.”

I was the beneficiary of some great programs like Head Start, obviously the Girl Scouts, but I also had really amazing teachers and mentors, and then I was able to develop skill sets that became extraordinary, that were able to give me opportunities like math, being able to have the kind of math skills to be able to re rocket scientist. It was a confluence of those things that I realized gave me this great opportunity to live a life of my dreams and my potential.

My Girl Scout troop leader taught me to never walk away from a sale until I’d heard “no” three times, and that was so transformational because I had been raised in a Spanish-speaking household and kids are not supposed to speak to adults until adults speak to them, that’s a really hard way to sell cookies. it taught me is persistence, resilience, and how do you get to the yes.

Big Ideas/Thoughts

My fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Baldwin, showed us pictures of universities in class one day, one of which was of Stanford. Remember I grew up in the desert Southwest, one of the most extreme deserts. There’s the Tundra, there’s the Sahara, and then there’s the Chihuahuan Desert, and that’s that part of New Mexico where I was raised. When I saw the green verdant hills and the red tiled roof and the limestone buildings, I just said, “I want to go there.” And I probably meant I just wanted to go there to see it, but she walked to my desk, and she said, “You know, Sylvia, it’s one of the best universities in the US and the world, and you’re a smart girl and you can go there.”

Impact of Girl Scouts

I had the goal and the dream, wanting to work in NASA, or be part of the space program, going to Stanford. I had those adult mentors. I had extraordinary skills and also I had that drive of wanting to leave that for something better.

As I mentioned, my family struggled with money and I was really fortunate that the troop leader that we had said I could be part and do everything, but I had to sell a lot of cookies and use my cookie funds for those programs, and that was so important because there were several things that I learned from that.

For people listening on the call, we all know how to do that, but for a kid who’s been raised in near poverty and the circumstances, I didn’t know how to do that, so that really was that light bulb moment that taught me that I could have my goals and dreams, which is also why in fourth grade, when that teacher showed me the picture of Stanford, I was able to say, “Okay, what do I need to do? I need to break it down into smaller steps.”

CEO of Girl Scouts of USA:

One of the Girl Scout mantras has always been leaving a campsite better than you found it. So, when I became the CEO I got to work!

We created 146 new merit badges during my four-years as CEO, more than at any other time in history, and we also grew the cookie program by about 80 million dollars as well. 126 of the new badges were STEM: coding, cyber. robotics, design thinking vehicles. We did a partnership with General Motors and some with NASA as well, 126 STEM badges that are just really great badges for girls to earn.

Competitiveness in the tech Job Market

When you think about semiconductors, you realize that they’re the brains and so much of what we’re using to drive and create and power our world.

If you think about the United States and you have a workforce of about a hundred million people, you think, “Okay, in our top 10% is 10 million. You now have a couple of countries; India and China, who can provide more than 10 million people who speak English fluently in our technology advance, and so there is a whole lot more competitiveness.

In addition, you have the dispersal of work, so work used to be done locally. For the United States, we had a lot of people who kind of figured, “Well, I just need to work near a certain location, and I’ll be able to have work, and not only that I speak English.”

Those two competitive advantages many ways have kind of gone away for many jobs, the competitive advantage of local proximity and the competitive advantage of English being a unique language. Yes, English is the language of business, but now there’s a lot more people speaking English so it’s just not a competitive advantage now.

Transcript

Hello and welcome to On Boards, a deep dive at what drives business success. I’m Joe Ayoub, and I’m here with my co-host Raza Shaikh. On Boards is about boards of directors and advisors and all aspects of governance. Twice a month, this is the place to hear about one of the most critically-important aspects of any company or organization; its board of directors or advisors, as well as the important issues that are facing boards, company leadership and stakeholders.

Raza: Joe and I speak with a wide range of guests and talk about what makes a board successful or unsuccessful, what it means to be an effective board member, the challenges boards are facing and how they’re addressing those challenges, and how to make your board one of the most valuable assets of your organization.

Joe: Our guest today is Sylvia Acevedo. Sylvia has [00:01:00] served as a CEO for a number of organizations and as a board member of a number of organizations, including Qualcomm and Credo.

Raza: Sylvia started as a rocket scientist and worked for NASA and then worked in a variety of engineering, sales, and marketing roles at major tech companies, including IBM, Apple, as well as startups.

Joe: Sylvia was a girl scout and later joined the board of the Girl Scouts of the USA and ultimately served as its CEO.

She has also served as a Presidential Commissioner on a White House initiative organized by President Obama for educational excellence for Hispanics and early childhood leadership. Welcome, Sylvia. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Sylvia: It’s great to be here, Joe and Raza.

Joe: You have an amazing story that leads to an amazing career. Let’s start with your backstory. One of the first things you said to us when we talked to you a few [00:02:00] weeks ago was that you were a devout believer in the power of transformation and disruption to change and improve lives, communities and organizations in the world.

Given your background. I’m not surprised you believe this, but could you share a little bit of growing up and what the circumstances were that led you from your beginnings to attending and getting an advanced engineering degree at Stanford University.

Sylvia: Well, thanks a lot, Joe. Yeah, I think because my whole life is like this amazing transformation story, because there’s another way of introducing me, you really highlighted some of the achievements I’ve had, and I’m very proud of those. But if I introduced myself a different way, which is a girl from a Spanish-speaking household who has struggled with money.

In fact, sometimes we didn’t have enough money, had to live with other family members, live paycheck to paycheck, and sometimes there wasn’t even enough money between the paycheck periods, [00:03:00] and then the only place we could afford was a home on a dirt street, and that’s where the last meningitis epidemic happened, and my sister got sick with meningitis and it forever changed her brain.

If you think about it, okay, here’s a girl from a predominantly Spanish-speaking only household, family struggles with poverty, lives in a really difficult area, how did that girl become the person you’re talking to today?

And so that’s why I believe so much in the power of transformation. It’s kind of interesting. I didn’t understand how many factors had kind of come into play. It wasn’t just my DNA, like I’ve got the drive, but there were just so many interesting aspects of organizations, people who really made a difference in my life, but I didn’t know that until the mid-2000s when there was a researcher from Stanford who was calling.

And she wanted to know how come it was that I went to Stanford because she said at the time, Stanford wasn’t recruiting in rural New Mexico. She wanted to know how I even knew Stanford, how I was prepared, [00:04:00] especially at the graduate level. You’re competing with the best of the world, and not only did I end up graduating, I ended up having this great career, and I didn’t have an answer for her.

But the more she asked, she said, “Were your parents academics?” No. “Were your parents wealthy ranchers?” No. She’s like, “So what happened?” And the more she kept asking. the more I realized I was really a beneficiary of some great programs like Head Start, obviously the Girl Scouts, but I also had really amazing teachers and mentors, and then I was able to develop skill sets that became extraordinary, that were able to give me opportunities like math, being able to have the kind of math skills to be able to re rocket scientist. It was a confluence of those things that I realized gave me this great opportunity to live a life of my dreams and my potential.

Joe: One of the things you told us was that early in your academic career, I think very early, a teacher showed you a picture of Stanford. [00:05:00] Can you tell us about that?

Sylvia: Well, yeah, I remember that very vividly. It was Mrs. Baldwin in fourth grade and she was sort of a visionary of her time. She showed us pictures of universities, and remember I grew up in the desert Southwest. That desert is one of the most extreme deserts. There’s the Tundra, there’s the Sahara, and then there’s the Chihuahuan Desert, and that’s that part of New Mexico where I was raised. When I saw the green verdant hills and the red tiled roof and the limestone building, I just said, “I want to go there.” And I probably meant I just wanted to go there to see it, but she walked to my desk and she said, “You know, Sylvia, it’s one of the best universities in the US and the world, and you’re a smart girl and you can go there.”

That nine-year-old girl in fourth grade made that a goal, and once you decide in a goal, then you start figuring out how to achieve the goal, and obviously getting really good [00:06:00] grades and being involved in lots of after-school activities, that was what I decided I would be doing because I really wanted go to Stanford, so I was very proud of the fact that I ended up actually graduating from Stanford as well many years later.

Joe: Wonderful to have a teacher that believed in you. I mean, what a great factor to have.

Sylvia: You’re absolutely right, and part of those for me, trying to figure out the answer to that Stanford researcher’s question, which is like, how did this happen? And I was fortunate enough to read a book by Dr. Ruby Payne called “Bridges Out of Poverty,” and she writes about how you need to have at least one of these things.

One is you have to have a goal and a dream, and clearly I had that, that dream of going to Stanford, but you could also have a mentor or a guide, and the challenge is that when you’re raised in poverty or near poverty, that’s what your community knows so you don’t know how to get out, because if you did, you wouldn’t be there, right?

It’s really important that you have people who can help you out, [00:07:00] and so though I had so many great teachers, my troop leaders, people who could help and advise me.

Another thing you need to have is or can have to help you get out is an extraordinary skill, and I was really fortunate that I honed my math skills to that level, but I also was really good in percussion in music, and I actually had a four-year scholarship in music that I turned down to study engineering, and then I also played basketball for one year on the varsity team, but then I decided to really focus on study, so I had extraordinary skills that way.

But then the fourth thing was it’s too painful to stay, and that was an important lesson too because I realized it was so important for me to have that drive to get out of that community where I was living.

Those were the four things, and I was really fortunate that I had all four of them. I had the goal and the dream, wanting to work in NASA, or be part of the space program, going to Stanford. I had those adult mentors. I had extraordinary [00:08:00] skills and also I had that drive of wanting to leave that for something better.

Raza: Sylvia. I want to then mention the book that you have written called “Path to The Stars:” My Journey From Girl Scout to Rocket Scientist.” I just sent it to my niece. I gave it to my daughter. I think it’s a wonderful read and really highlights that journey to inspire our children and especially girls all around.

Sylvia: Well, thank you so much, Raza. Yeah, I wrote that book because one time I was talking at a school, and it was in a large auditorium, and then afterwards there was a really long line and I thought it was for lunch and the woman said, “No, that’s not for lunch. That’s for people who want to talk to you.”

Being an engineer, you want to scale and I realized, “Today, I have time to be able to talk to all these kids, but in the future, I’m not so sure that that really scales.” So, I decided to write that book and I’m really grateful that I did. It’s continuing to sell really well. Schools are adopting it into their curriculum and it’s very much a middle school [00:09:00] memoir.

I chose middle school because the way the world is evolving, science and technology are embedded in everything that we’re doing, and you need to have at least a modicum of understanding about science and technology, and middle school is kind of that last time you can choose those electives and that really what is like an inflection point in your life.

I think about an elevator door closing and my book is like stopping those elevator doors from closing and hopefully the kids will read it and get inspired to study more math, science, and just get involved in and just the wonder of how the world is being recreated around us.

Joe: Can you talk a little bit about the impact that the Girl Scouts had in your early life and ultimately in your career, of course.

Sylvia: Yeah. Sure. I’m very grateful for that experience. As I mentioned, my family struggled with money and I was really fortunate that the troop leader that we had said I could be part and do everything, but I had to sell a lot of cookies and use my cookie funds for those programs, and that was so [00:10:00] important because there were several things that I learned from that.

One, since I wanted to do everything I had to sell a lot of cookies and the numbers seemed really incomprehensible to me, but what she did is she said, “Whenever you have a goal or a dream, you set that goal and then you break it up into smaller parts,” and so we said, “Okay, we’re going to sell cookies for six weeks.” We divided the number by six, and then I said I was going to sell six days a week so we divided that number by six, and so the daily goal was very achievable and so that was really helpful, but she also said, “You could always ask for help.”

For people listening on the call, we all know how to do that, but for a kid who’s been raised in near poverty and the circumstances, I didn’t know how to do that, so that really was that light bulb moment that taught me that I could have my goals and dreams, which is also why in fourth grade, when that teacher showed me the picture of Stanford, I was able to say, “Okay, what do I need to do? I need to break it down into smaller steps.”

But the other thing that that troop leader taught [00:11:00] me was to never walk away from a sale until I’d heard no three times, and that was so transformational because I had been raised in a Spanish-speaking household and kids are not supposed to speak to adults until adults speak to them, that’s a really hard way to sell cookies.

The first time I’d gone up to somebody who I didn’t know, wasn’t a family member or somebody at church, would you like to buy some Girl Scout cookies, and she said no, and I stood there looking at her and she looked at me like, “I said no,” and so I asked again, “Is there anybody at your house that would like to buy some Girl Scout cookies?” And she said, no. And again, I just. stood there rooted in place thinking, “Troop leader said never walk away from a sale until you’ve heard no three times.” Then I said, “Is there anybody who I could meet?” And she bought a box of Girls Scout cookies, probably just to get rid of me.

But what it taught me is persistence, resilience, and how do you get to the yes, and I will tell you that that is a skill that has helped me in my [00:12:00] entire career, because I’m a trailblazer. I’m really fortunate to have been able to have a lot of doors of opportunity open for me, and I was the first one through those doors. As a trailblazer, sometimes it’s kind of tough and you hear no a lot, and so I’m trying to figure out how do I turn that no into a yes was a skill I began developing, creating opportunity and getting that no into a yes. I was working on that skill since I was seven years old.

Joe: It’s amazing and great advice and kudos to the Girl Scouts.

I will also add, though, you said very early on, it’s not a matter of DNA or something like that. I think it’s clearly a matter of DNA because a lot of people could have heard this “you have to ask three times before you give up” and and thought to themselves, as I think most kids probably do, “No, I don’t.” But you actually did it and I think it’s amazing, so it’s really everything coming together. I mean, there are obviously people in your [00:13:00] life and the Girls Scout organization that really, really not only taught you persistence, but one of the things that, as I recall, that you learned there was you deepened your interest in science. You wanted to get those science merit badges Talk about that for a minute.

Sylvia: You’re absolutely right. Yeah, I was still a girl and I earned the cooking badge just like all my friends, but my troop leader had remembered me looking at the stars when we went camping one night and she taught me about planets, that there was the constellations and there were planets and stars, and so later she encouraged me to earn a science badge and also incorporate space into that. So, amongst several of the things that I did to earn that badge was making an Estes rocket and having it successfully launched, and I tell you, I failed a lot of times, and that’s also kind of a benefit of an all-girls environment, which is if I had been, I think, in a coed environment and I had failed three times they would’ve probably said, “You know what? I [00:14:00] don’t think this is for you,” and then the fourth time I failed or the fifth time I failed. But the sixth time, I finally got that rocket going up into the sky and I had that sense of achievement, like I can do this, and it really filled me with this confidence that I had that I could then do science and math, and so I’m really grateful for that opportunity.

Joe: So, later, after being, I’m sure, a standout girl scout, you actually joined the board of the Girl Scouts. How long were you on the board, and then tell us what happened as you served on the board?

Sylvia: Yeah, I was on the board for eight years. I was very grateful, and actually the former Governor of Texas ,Anne Richards, I was on a board on a school that was named after her, the Anne Richards School for Young Women Leaders in Austin, Texas, and I had told her about my Girl Scout experience, and so she nominated me to be on the national board, that I was really grateful to serve. When I was on the board after my eighth year, the former CEO, she had gone to pursue other opportunities and the board asked me to step in.

Now I had [00:15:00] just moved to Santa Barbara from Austin, and so the national headquarters is in New York and I said, “Okay, I’ll just do this until we find somebody else.” But one of the Girl Scout mantras is always leave a campsite better than you found it. So, I got to work and I was there until I wasn’t there.

The other thing is I had been on the board for eight years and I wasn’t an operator then, but I was just the strategy and governance, but in my head, I would have this kind of exercise saying, “Well, if I was the operator, what would I do?” When I became CEO, I had had like eight years of like, “Here’s what I would do,” so I immediately started focusing on things like the cookie business and so we completely rearchitected the cookie program, and then also those badges. We hadn’t really been on a fast implementation level and we ended up adding 146 new badges in my four-year time, more than at any other time in history, and we also grew the cookie program by about 80 million dollars as well.

I was really [00:16:00] grateful for that experience, but I had gone one year and by the fourth year, it’s the time for the three-year trieannum, and so it was a good time to sort of hand the mantle over to the next leadership level, and now I’m focused very much on technology.

Joe: Just the Girl Scouts, the badges you added, were any of them science and math field?

Sylvia: Oh, my gosh, so many of them were, 146 were STEM. I’m really proud of that because we really wanted girls, not just to be users of technology, but creators, inventors, and designers, and so many of them have mobile devices, so they’re coding, cyber. robotics, design thinking vehicles. We did a partnership with General Motors, so just so many amazing and obviously some with NASA as well. Those were some of my favorite badges, so 126 STEM badges that are just really great badges for girls to earn.

The cybersecurity really surprised us of how popular they were. The first year we had cyber badges, a [00:17:00] 180,000 of them were earned in the first year, but then when we dug into that, it turns out girls were very concerned about their personal safety using mobile devices, and so really learning about how to protect themselves on cyber. In addition to that, we had badges in the great outdoors with the partnership with North Face, as well as civics.

Unfortunately, civics has been taken out of so many American classrooms and so we wanted to make sure that girls understood how our democracy and our Republic works, so I was very proud of those badges as well. But all the STEM badges, you bring up a really good point with that, is that we had to rewrite the curriculum because what we found was much of the STEM curriculum that has been written has been designed around what interest boys, and so we had to redesign the curriculums around what interested girls. It’s the same scientific principles, but just in a way that was much more engaging. And as a result of that in my last year, full year in 2019, over a million STEM badges were earned.

I have to say something that’s just so great.

[00:18:00] Just recently I was in San Diego and this young woman who, the maître d at the restaurant, she came up to me and she said, “I just want to thank you. I got my start in STEM with Girl Scouts, and now I’m studying to be a marine biologist. It just feels really wonderful to know that you’ve got that kind of impact.

Joe: Well, I think when we talked about this earlier, I had mentioned that my daughter had applied to school for engineering and when we looked at some of the schools, I was stunned. Now, this was in 2013. I was stunned at how few women or girls were applying for those classes, were sitting in those classes. She ended up going to the University of Colorado at Boulder for aerospace engineering. And that first year she was surprised, as was I, at how few women were in the class.

One of the things you touched upon when you talked about changing the curriculum for the Girl Scouts, which is there’s a cultural bias towards how science is taught. [00:19:00] Could you just talk about a little bit about that? Because I really had a hard time understanding. Are we still discouraging girls? But it’s a little more complex than that, I think.

Sylvia: Yeah. It is. I looked at it from three things. First, you have to have an interest and you’ve got to get the girl interested, and then you build the confidence, so you’re interested and you’re confident, then you work on the competence. A lot of people like to include Legos and think, “Okay, those blocks are gender neutral.” But I’ll give you a really great example because most boys of a certain socioeconomic level in the United States get Legos by the time they’re three years old, and so by the time they get to elementary school, they’re very confident with Legos. Girls don’t get Legos usually for gifts.

Let’s just say, there’s this incredibly well-meaning third grade teacher who wants to do STEM exercises. She says, “I’m going to use Legos because I want them to be gender neutral.” Well, the boys’ eyes light up because mostly in girls, especially in elementary school, they’re [00:20:00] outperforming the boys. Here, they’re going to use Legos. They’ve been doing Legos for many years, for five years now, so they immediately get to work with the Legos. The girls they’re thinking, “Okay, I’m not as familiar with Legos. What am I supposed to do? How am I supposed to do it?” And then they see the boys and they’re normally outperforming the boys, and the boys are like finished and doing more, and the girls are like, “Ugh.” So, they’re not really that interested, and then, because they’re not interested, they’re not that confident, and then they don’t really pursue it to be competent.

Now in Girl Scouts, we work with Legos but we did it in an all-girl environment so that everyone was starting at the same level, right?

But for other things like cybersecurity, like we taught about malware and networks, like how do you teach a seven- and eight-year-old to be interested, confident and competent on malware and networks? It’s like that’s crazy. Well, actually we were amazingly successful at that so when we get seven- and eight-year-old [00:21:00] girls to sit in a circle and talk it turns out they love to do that, and they’re talking with one another. Well, you get a ball of yarn and they pass the ball of yarn with one another as they talk with one another, so within a very short amount of time, the girls have created a physical network.

Then you also say one of the girls had a virus and they can immediately see how that virus spread through that network, so suddenly they’re interested. They’re confident and then they work on their competence, which is kind of back to that point when I said our first year, a 180,000 cyber badges were earned. Really designing things around how the girls are interested and then work on that for confidence and then build on the competence of it.

Joe: It suggests that a really significant and deep cultural change in [00:22:00] the way we educate is really what it’s going to take, because everything you said made perfect sense, but it isn’t necessarily intuitive so it’s going to require thought and deep change in how we teach in order to really find gender parity in STEM. I mean, that’s what we should be looking for, I think, right?

Sylvia: Well, we desperately need the talent workforce, that’s for sure, in the United States, and cyber in particular because we very much need to protect our assets and protect our democracy, our country, our communities, our homes, our institutions, and so you need talent at every level. You need them at the local level. You need them at the national level, at the state level. Hey, you need that kind of talent protecting our home computers and information at home. We need to have a lot of people that are very interested and aligned about what our national interests are to protect us.

Raza: Sylvia, you did your advanced engineering degree at Stanford, [00:23:00] and then you were looking for a job. Tell us how you ended up at IBM and then your journey from there among various well-known tech companies, and how did you find that environment for you and how you progressed through that?

Sylvia: Well, thanks. I have to say that was back in an era, technology has improved, maybe not as many of us thought it would’ve changed by that time. But back then, it was incredibly challenging. I graduated from Stanford seeing a lot of my classmates thinking the world is our oyster. Silicon Valley was just taking off. That was the ground zero. They were getting job offers left and right. And these are in the back in the days where you printed your resume, I kept printing and printing and handing out and networking, and I thought this is really tough, well over a hundred resumes.

I went to like every networking event and it was incredibly difficult. Some of my friends were just getting these amazing jobs and companies, and I just couldn’t break through. Fortunately I did finally get a job as a [00:24:00] facilities engineer at IBM and that wasn’t exactly what I thought, having worked at NASA as a rocket scientist, but it was the foot in the door I had and I was really grateful for that foot in the door. I took that approach and I thought, “How do I really make this opportunity work for me?” I really began thinking about how can I provide innovation?

In that facilities engineering role, especially in a manufacturing facility, they kind of just thought of facilities engineers as just moving the pieces and just making sure that it meets OSHA standards and there’s tolerances, people’s safety and all that stuff. But I took a different tact, I did do designs that fit that standard, but I also said, “How about if we tried some innovation?”

I actually went and worked and talked to the machine operators and the women who were actually assembling the parts and they had some really creative ideas. When I presented my idea, I presented what was the standard way of solving the manufacturing workflow, but then I also put in their innovative [00:25:00] way, and I remember the head of manufacturing, he looked at that and he goes, “looks really interesting. Let’s try that innovative approach,” and production shot up.

Well, lucky for me, IBM was then in the process of building a very large manufacturing facility there in San Jose, it’s 765,000 square feet. I still remember it to this day, and because of that experience, the big manufacturing boss asked for me to be the design engineer. I was able to do a standard approach, but then I also added a really new innovative approach, and that became such a showcase for IBM that actually they would bring the different stock analysts to see the big manufacturing plant. That was because it was really innovative back in the day.

That then got me to the IBM Charm School the marketing and sales program. I had talked to my boss about I wanted to be one of those big execs and he laughed. But remember, by this point, his laughter to me was just one of the first [00:26:00] nos. I’m like “Okay, how do I get to a yes here?” I said, “Well, imagine if it was a possibility, what skills would I need to have?” He mentioned sales, marketing, and all that.

Well, I did get into that marketing program. It took me a really long time to break through. I remember his first name, I don’t remember his last name, but I knew there was an opportunity in a Silicon Valley, in the Palo Alto office, and the guy George, who was the gatekeeper, I called him so many times. I met with him, and finally I broke through and got into one of those coveted spots. I did really well at IBM, a hundred percent club, got to ride the company jet, all sorts of great things.

Then I went to work at Apple and other places, but one of the things that you’re alluding to, which is really true, is that I was doing incredibly well and I wanted to change divisions and I wanted to move into the international field. I thought there’s great opportunities, and this international division also has Latin America as part of it and they speak Spanish and [00:27:00] I can speak Spanish, so I thought it was a good fit.

Well, I’ll tell you that nothing, crickets. I would apply for positions, nothing, and month after month after month, and I would see these positions and some of them would get filled, many would not get filled. I talked to the HR folks. I talked to people, nothing, so I thought about that and I thought, “Okay.”

This was back in the day before really advanced CRM analysis, but I pulled a Fortune of 500 Global. I think in the summer they always print this out and I looked at all these different accounts and then I saw that these global accounts, that we had global arrangements. They were underfunded and under penetrated in the sales in the global business or the Pacific region.

I did an analysis showing that if they had the same kind of penetration with these global accounts, like the Fords, the Proctor and Gambles, et cetera globally as they did domestically, it would be hundreds of millions of additional sales. I [00:28:00] did a PowerPoint presentation. I printed it out, and because I worked in the company, I was able to badge in and I waited for the head of sales, this gentleman named John and I got him right outside the elevator lobby and I said, “Hey, John, I’m Sylvia Acevedo and I can show you how you can increase sales by several hundred million dollars.”

He looked at me like, “Interesting.” He goes, “Okay, I’ll give you five in the team room,” so we got a team room and he flipped through the PowerPoint presentation and he was like, “Whoa.” He just had not considered that and so he goes, “This is great.” He went to take it and I put my hand on it. And he said, “Can’t I have it?” I said, “Well, it comes with me.” And that’s how I finally broke in.

I’m really grateful that I did. I had a really great experience in that working internationally, which then opened up for other opportunities, at Autodesk and other places where I can work in international markets.

Raza: Well, it looks like you became a well-rounded technologist but in all of these different instances, the [00:29:00] lesson of never go away from a sale until you hear no three times really paid off very well.

Sylvia: Yeah, it did. And by that time I’ve got that persistence, that resilience and trying to figure out, “Okay, this approach isn’t working. How am I trying this approach?” And having that goal and that drive to really want to have that experience was really important.

Raza: Sylvia. Now, you are a board member at Qualcomm and Credo. Could you talk about what these companies do and a little bit about the board and how it’s composed for each.

Sylvia: Sure. So, Qualcomm, I think a lot of people know because of the 5G, so think about wireless, so those chips that enable the mobile technology and communications, that’s Qualcomm, so wireless. Credo, it’s completely, technology semiconductor, but everything wired. When you think about server farms and you think very high density, server blades, they’ve got to be physically connected and so Credo has amazing technology that really speeds up [00:30:00] the rate of transmission, but not only that, it saves energy and produces less heat, which is really important when you’re thinking about server farms and the amount of heat and electricity that they consume. So, that’s Credo Technology and then Qualcomm.

Qualcomm is obviously a much bigger company, with over 35- to 40-billion global business. Credo is growing now, we just went public this year. One of the few technology companies who’ve gone public and whose stock is above water so that’s all really great. Credo has still some of the early investors and then has added some technologists and other independent board members like myself. The board chair, Lip-Bu Tan, formerly of Cadence and he’s kind of a legend in technology. I think he’s been part of like a hundred-plus startups himself and companies that have gone public, so a lot of great experience and the CEO, Bill Brennan, a real semiconductor superstar.

On the Qualcomm side, a very large company. We have a great CEO as well. Cristiano Amon, he’s [00:31:00] actually a Brazilian, and he has been in Qualcom for quite most of his career. The board has many former CEOs. It’s got a balance of global as well as domestic and across industries, which I think is very important because we’ve got technology embedded in cars now, in robots, on industrial floors and everything, so it’s really important to have a well-balanced board. And the board chair there is Mark McLaughlin who used to be in Palo Alto Networks, and he’s really an amazing and a great steward of that board as well.

Raza: It sounds like a really good diverse perspective board. How does the board see what’s top of mind today vis-a-vis, let’s say, competition with China or ESG? What are some of the things that keeps the board busy?

Sylvia: You’ve really hit on it quite a few. If you’re in technology and in semiconductors, China is clearly top of mind, and then following that very closely and very intertwined with that is also the global [00:32:00] supply chain, which has definitely been fragmented in how are you sourcing now so huge issues, and then that’s also tied into ESG as well, so all these things it’s like they’re all braided together.

When you think about semiconductors, you realize that they’re the brains and so much of what we’re using to drive and create and power our world. And in the US, we had outsourced so much of that technology and so now there’s a huge effort of bringing that back, especially with the government’s recent passage of the CHIPS Act, you really see that. When you’re on a board that has something to do with semiconductors, there’s always something about the news headlines that is impactful to what you’re doing.

The other aspect too is staffing. Again, when you think about the global supply chain, it wasn’t just in parts and supplies, it’s also with talent and it’s so important now to make sure that in the United States, we’re also sourcing local talent because the immigration laws have been [00:33:00] changing and so you’ve got to make sure that you’ve got your own home-grown talent as well, because for some of these positions you’re not going to be able to get talent from outside the United States. Talent is a big, big issue and then with the lasting impacts of the hybrid workforce, it’s like how do you restructure work? How do you think about work? Those are also things that at the board level, we’re thinking a lot about.

Raza: In terms of talent, is there a skill mismatch. I’m now talking at the national level. How are large companies such as Qualcomm finding that, and how are they grappling with that?

Sylvia: Yeah, it’s incredibly competitive. That’s certainly the case. It’s very, very, very competitive. And what you’re starting to see is more and more universities partnering with corporations so that you begin to develop that talent pipeline, and then you think about where can you outsource certain kinds of work. With semiconductors, you really need certain kind of talent because you are making a chip. I know people say, “Well, why can’t we just build a chip plant?” And I think it’s [00:34:00] like, “Well, it’s like planting at oak and saying, “Just produce acorns.” Now, it takes a lot of time, but it’s not just the time. It’s the expertise. It’s not just the machine quality and the machine accuracy that you need, but you also need people who really understand what it takes to make semiconductors, especially when you have such thin, thin, thin, extreme tolerances.

There’s that whole ecosystem, and you’re seeing more and more partnerships. Clearly like Intel going to Ohio and partnering with The Ohio State. You could see that there’s going to be a very close alignment there. They’ve also very much partnered with ASU in Arizona. There’s quite a few chip plants there as well.

You really do have to think about that talent, and I think that’s back to our earlier discussion about getting women in STEM that that’s so important that they see that they can have a career, that this is an environment for them. This is where they can live their life potential working in these companies, and that’s very important. You’ll see a renewed emphasis on that. [00:35:00] I think, with most technology companies, you’re going to see that, especially for the cutting skills.

Raza: But in terms of developing skill, one thing that you had mentioned earlier was the role of the English language. Talk about that a little bit.

Sylvia: Yeah. This is something that for the United States, we’re really proud of the fact that we can go around the world and people speak English, and it’s like great. But it wasn’t always that way, and English used to be that premier language, and so if you spoke English, it gave you a competitive advantage.

Well, several countries, back in the 20th century, went back and said, “Okay, we’re going to put a focus and make sure that we have top engineering schools, but not only that, that people speak fluent English as well.” And these are very large countries, so when they say 10% of their population is going to be speaking English fluently, you certainly have got tens of millions of people who can speak English fluently, and then [00:36:00] also graduate from engineering schools.

If you think about the United States and you have a workforce of about a hundred million people, you think, “Okay, in our top 10% is 10 million. You now have a couple of countries; India and China, who can provide more than 10 million people who speak English fluently in our technology advance, and so there is a whole lot more competitiveness.

In addition, you have the dispersal of work, so work used to be done locally. For the United States, we had a lot of people who kind of figured, “Well, I just need to work near a certain location and I’ll be able to have work, and not only that I speak English.”

Those two competitive advantages in a lot ways have kind of gone away for many jobs, the competitive advantage of local proximity and the competitive advantage of English being a unique language. Yes, English is the language of business, but now there’s a lot more people speaking [00:37:00] English so it’s not just a competitive advantage now.

If you turn that coin around on the flip side, sales and service are always done in the local language. Yes, somebody may speak English in another country, but sales and service is done in their home language, and so the United States not having that talent of having a very large bilingual population really puts you at a disadvantage when you’re saying, “Well, now, I’m going to take the great opportunity and go to those countries,” and you find that your English-speaking skills work really well in the business environment, but not in the sales and clearly the service area as well.

That has been a big change for lots of folks and they don’t realize that now there are tens of millions of people competing for their jobs, and especially if your job is not required to be geographically proximate anymore. That means it’s untethered and can go anywhere, and so that is a huge challenge for a lot of American workers, and I think that’s something that has to be addressed [00:38:00] educationally and also expanding on our ability to speak more than one language is also key.

Joe: Let’s go back for a moment just to the CHIPS bill, which really has got a lot of play lately. What role did the companies on whose boards you serve, what role did they play in trying to help get over the finish line, so to speak?

Sylvia: Well, I think every semiconductor company had a role. Every hand was on the boards. In fact, Pat Gelsinger was at the. State of the Union address with President Biden and he’s the CEO of Intel, so everyone was trying to get this across the finish line because it’s so important. It’s important from a military perspective, it’s important from an economic, it’s important from an industrial policy perspective. It’s also a great economic development boost for the different parts of the United States with the chip fabrication plants and the design.

I think that it’s incredibly beneficial. We have outsourced some of the leading edge chip capabilities and [00:39:00] trying to figure out how can we bring that back in, and when you talk to folks, it’s a 47-year timeframe that we’re looking at. It’s not immediate, but along with that is also the importance of cybersecurity. And the US, it turns out is really good at cyber offense. We’re extremely good at cyber offense, and I think that should make us feel definitely a lot more comfortable. However, we’re not as good at cyber defense, and that for all of us is a challenge.

We as Americans love our freedom and we love to have everything connected. Our microwaves are connected to, you know. Even our refrigerators tell us when we need additional milk and other products so we’ve got everything connected to our mobile devices. But that also means that those are all points that could be attacked by someone who wants to do us harm, especially for small- or medium-sized businesses that serve really large businesses.

The large businesses, large corporations, they really spend a [00:40:00] lot of effort focusing on cybersecurity, but think about the companies that are like the heating and air conditioners that come in to support you. You have to give them access to your building. They may have some of those codes on their computers back at work and not necessarily as protected so there’s lots of different ways of thinking about how do we protect ourselves here in the United States, and so that’s more of the cyber defense.

Of course, a lot of people don’t want to have government regulation and forcing us to have so many network protections, but you can see that’s all part of figuring out how do we protect ourselves in the United States. So, we’re great at cyber offense, it’s really working at how do we protect ourselves domestically on the defense side.

Joe: Sylvia. It’s been great speaking with you today. Thank you so much for joining us, and thank you all for listening to On Boards with our special guest, Sylvia Acevedo.

Raza: Please visit our website at OnBoardsPodcast.com. That’s [00:41:00] OnBoardsPodcast.com. We’d love to hear your comments, suggestions, and feedback.

Joe: Please stay safe and take care of yourselves, your families, and your communities as best you can. We hope you’ll tune in for the next episode of On Boards. Thanks.